What is an IPO?

An IPO, short for an ‘initial public offering’, occurs when shares in a privately held company are first listed on a stock exchange.

The first modern IPO took place on the Amsterdam Stock Exchange in March 1602, when the Dutch East India Company sold shares of the company to the public, making it the first ‘public’ company (sometimes referred to as a ‘listed’ company). Once an IPO is complete investors can freely buy and sell shares on the market (a stock exchange) provided there is a person/group/fund willing to complete the opposite action at the set price.

Why are investors interested?

The bump

The 'IPO bump' is a term applied to the immediate rise in share price a stock experiences shortly after listing. Seeking Alpha reported the bump for biopharma companies to have been 141% in 2016 – an amazing return if you can get it. But the truth is that for every company that gets a good bump, there are many more that do don't or, worse, go in the other direction.

The hype

The media loves to cover IPOs of tech and not-so-tech darlings; whenever there's IPO rumours of a potential company float, you’ll see a lot of coverage in the news. Rumours are fun, but they don’t always come to fruition – and when they do, the buzz around the company can lead to interesting consequences for the share price. Take Snap Inc, the company behind Snapchat, as an interesting case study. While the stock price got a nice bump immediately following the IPO, just three months later the stock was trading well below that share price.

How do companies conduct an IPO?

A company ‘goes public’ to raise finance for its business. An IPO is also a valuable opportunity for the company to raise its profile and generate publicity, attract public market investors, and demonstrate to its investors that it will be submitting itself to a rigorous corporate governance and reporting regime.

It can take up to a year of preparation to get a company ready and then two months or so of marketing. But what does the company do during this time and why is it necessary? There are two phases of an IPO process:

The preparatory phase (lasting from four months to one year):

The preparatory phase gets the company ready to be a public company from the corporate governance, budgeting, working capital, personnel, IT systems and PR/IR perspectives. This might involve new hires, and changes to lots of systems and controls. The company also appoints several advisors (at some expense). One of these – the investment bank/broker – will help the company understand how much it might be worth and how much it might be able to raise. The investment bank might also introduce the company to a select group of investors (normally between five and 20) to gauge interest.

The company and its advisors will draft all the marketing documents, one of these being the IPO Prospectus, which contains all the information necessary for investors to make their investment decision. All investors get to see the Prospectus ahead of investing.

The formal marketing phase (typically lasting four weeks):

Public company shares have a market-derived price based on publicly available information: information that has been disclosed by the company, reported by analysts, and all sorts of macro and sector data.

As private companies have limited disclosure obligations, financial analysts do not cover them and, more often than not, the press does not pay them a great deal of attention. The aim of the marketing phase is to get as close to an equivalent market derived valuation as possible. Once the company is fully prepared and the Prospectus is in advanced form, the formal marketing phase of the IPO kicks off with the publication of the Intention to Float announcement. At the same time, the investment bank’s research analyst publishes their research note and circulates investor contacts.

Settlement and beyond

Following settlement, the company and investors want to see a small rise in the share price, which demonstrates that the company has been properly valued.

Most companies will want to raise capital at some point post-IPO. To do this effectively, a company will need a strong group of supportive shareholders. To develop this group, the company must ensure that it hits its promised targets, which were made during the marketing process, and that it reports in a timely and transparent manner on an ongoing basis.

An IPO is an important step for a company, but it is the first step in the public markets. All this preparation and marketing ensures that at IPO the company is well positioned to succeed on the next stage of its development.

How does an IPO work?

The process a company must undertake to list on the stock market is often long and expensive. A lot has to happen behind the scenes before investors even find out about the opportunity to invest. The company must appoint a broker, an account, an auditor and sometimes a lawyer or team of lawyers, and so on. The company has to put together a set of audited accounts, file and submit forms to the regulator and market, and generally undertake a huge amount of tidying up before investors are given even the slightest hint of a potential investment opportunity. All of this behind-the-scenes magic can be read about elsewhere. Here we start the process from the point investors can get involved.

It starts with a rumour

Given that the IPO process can take a long time, sometimes many years, and that a company must appoint a large number of advisors/service providers to assist with the process, investors often catch wind of a potential IPO well before it is actually officially announced.

Rumours may be triggered by a company appointing a new accounting group as its auditor or hiring a copmany like Goldman Sachs as an advisor. These actions in and of themselves do not necessarily mean that a company is intending to float, but they all add fuel to the rumour-mill fire.

Intention to float

When a company is going to float, it will formally announce its intention through – you guessed it – an intention to float (ITF). This can take place somewhere between a few days and a few weeks prior to its expected listing date.

An ITF includes a brief summary of the company, the amount it is seeking to raise and a rough timescale outlining when the offer will likely open, when it will close, when allocation will take place and when the shares will be listed onto the market.

Invest during the offer period

This is the period during which investors get the chance to review more detailed information about the company and ultimately decide whether they want to invest and how much they would like to invest. During the offer period, no individual investor knows how much other investors are interested in throwing into the round; the amounts raised and received are only made apparent during the allocation period.

Allocating the shares

The broker’s job is to ensure that the company raises the amount it requires to float and carry out its intended activities. To make sure the target amount is achieved, a broker will often take more orders for shares than there are shares on offer. This is why you may here that an offer has been 'oversubscribed'.

When this happens, investors will not receive their full order for shares but rather an allocation determined by the broker. Sometimes allocation is straight-line, i.e. everyone receives the same percentage of what they ordered. Sometimes there is a cap on the amount anyone can receive, as was the case when the government was selling shares in Lloyd’s Bank. Sometimes there is a mix – everyone receives their full order up to £10,000 worth of shares and then they receive 50% of the next £50,000, then 10% of the next £100,000. Sounds strange, but there is method to the madness.

Admission to market

Once the shares have been allocated and all of the i’s have been dotted and t’s crossed, the shares will be admitted onto the market and investors can buy and sell shares on the open market. Occasionally, some of the larger investors will be unable to sell shares from admission as there may be a holding period associated with their purchase. This is often used, particularly with smaller companies, to stop the market from being flooded with shares, which would cause the share price to drop significantly.

In addition to larger investors, founders and employees are also often held to a holding period during which they are unable to trade. This holding period rarely applies to the retail investors who purchased shares in the open offer.

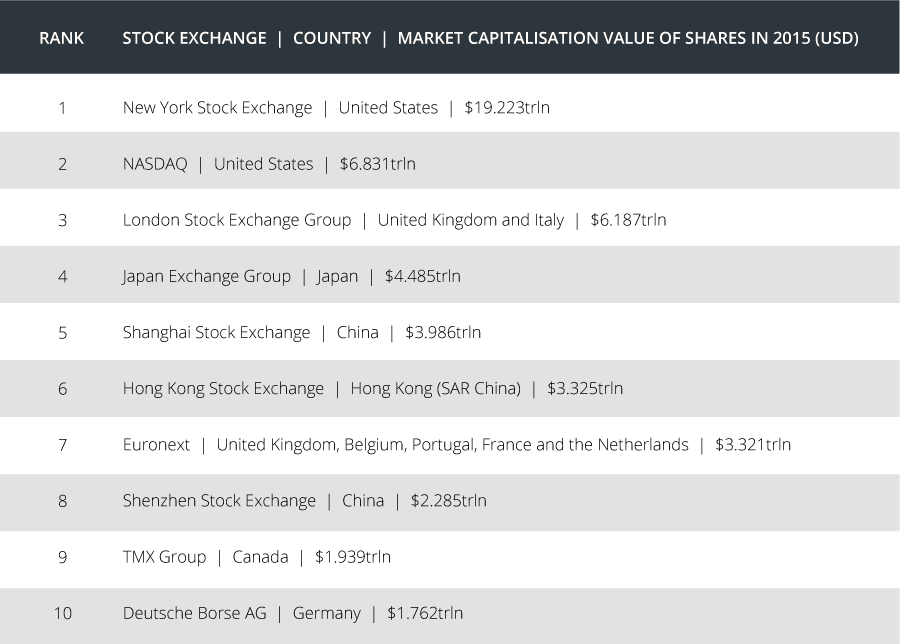

International stock exchanges by value

How to invest in an IPO

The decision of whether or not an IPO will be available to retail investors sadly rests with the brokers, and if they want to spend the additional time and effort putting together the relevant documents, and going through the steps needed to open the offer up to retail. Unless the broker can see a big benefit to having retail investors involved, they are unlikely to choose this path. In fact, the London Stock Exchange recently published some dire figures around retail involvement, showing that less than 20% of IPOs included a retail tranche. Our own report on the subject, Bridging the equity divide, is also available for free download.

So, what can you do? There are a few things, namely, pay attention to the rumours and make your voice heard. Let your broker know that you want to be involved and try and drum up some support amongst your fellow investors.

Additionally, you can approach the company directly as the final decision will come down to them. While brokers may shy away from retail, companies might want individual investors involved. It may feel like a war of attrition – or perhaps more like trying to topple a castle with a slingshot – but every movement needs to start somewhere.

Lastly, instead of waiting to find out if a company is going to have a retail tranche at IPO, you can pre-empt this and aim to invest in the pre-IPO rounds. This can be done through a fund, through a private angel investment or through an online investment platform like SyndicateRoom.